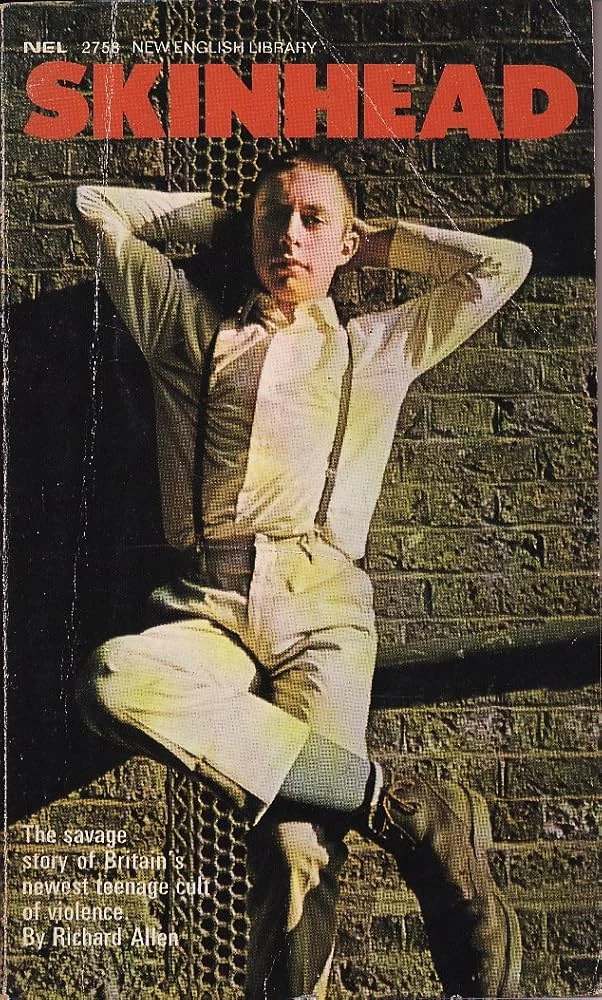

At SKNWRLD we’re starting a new series digging through Richard Allen’s infamous skinhead books, one by one, in the order they were first published. These pulp paperbacks caused outrage in the 1970s, spawning headlines, moral panic, and a cult following that never quite faded. At the centre of it all is Joe Hawkins, the East End teenager whose violent swagger became both a caricature and an archetype of skinhead life. We begin at the beginning: Skinhead (1970).

Richard Allen’s Skinhead dropped in 1970 like a cheap lager bottle smashed on a pub floor. It was the book that introduced Joe Hawkins, a sixteen-year-old East Ender who lived for West Ham, sharp clothes, heavy boots, and bovver. Written in breathless, lurid prose, the novel reads less like a literary attempt and more like a tabloid in paperback form, designed to shock middle England while giving working-class kids something they recognised – if only in fragments.

The opening chapters set the tone. Joe is introduced against the background of Plaistow, already at odds with his old man, already itching for aggro. He slips into his uniform—boots, braces, army trousers, union shirt—and heads out for football trouble. From the very first pages, Allen sketches a youth culture that was already being stereotyped by newspapers: violent, racist, lawless. Yet there’s also a detail in the gear, the talk, the pubs, that rings true to the era.

The book’s narrative isn’t complex. It’s more a series of violent episodes: football clashes, pub fights, racial attacks, sex, and petty crime. Joe moves with his mob from one scene to another, leaving broken faces and broken glass in their wake. The pace is relentless. Dialogue is clipped and full of expletives. Description is minimal, except when it comes to boots connecting with bodies or fists slamming down. It’s not crafted literature, but it is effective in painting a grimy, aggressive portrait of late-60s East End youth.

One of the key fascinations with Skinhead is how it blurs the line between documentation and exploitation. On the one hand, Allen clearly did his homework: he nails the obsession with football terraces, the distrust of authority, the hostility toward immigrants, and the pride in local identity. On the other hand, he turns every incident up to eleven. The violence is not only constant but gleeful. The sex is crude and transactional. Joe is never softened into a sympathetic anti-hero; he is an unapologetic brute, almost cartoonish in his brutality. That very excess, though, is what made the book stick.

For readers in the 1970s, Skinhead carried a double charge. To the establishment, it was dangerous pulp corrupting youth. To young readers, it was validation—a book that said their lives were worth putting into print, even if through a distorted lens. Skinhead culture at the time was already splintering, with reggae-loving original skins on one side and harder, more violent factions on the other. Allen chose the latter, and in doing so he helped cement the public perception of skinheads as thugs.

It’s important to note the context. Britain in 1970 was a country in decline: industry fading, unions clashing with government, working-class estates under strain, and immigration sparking fierce debate. The book reflects that, but only through Joe’s sneering eyes. There’s no balance, no other perspective – just a youth who despises his parents, loathes authority, and thrives on mob rule. Critics at the time condemned the racism and sexism in Allen’s work, and rereading it today it’s impossible not to recoil at some of the language and attitudes. Still, as a snapshot of a certain brutal street culture, it remains unflinching.

Stylistically, Allen is not a writer of finesse. His prose is blunt, repetitive, and often clumsy. But that roughness is part of its impact. It feels like the book itself is booting you in the ribs, refusing to let up. Where it falters is in depth—Joe never grows, never questions, never doubts. He is pure id: violence, lust, and tribal loyalty. That makes the novel both monotonous and strangely hypnotic.

It feels like the book itself is booting you in the ribs, refusing to let up.

Looking back, Skinhead is less about skinhead culture in all its complexity and more about one tabloid vision of it. There’s no reggae soundtracks here, no detailed look at style beyond the basics, no exploration of the working-class pride that shaped the original movement. Instead, it’s bovver boots, West Ham scarves, and endless aggro. Yet this very narrow lens became the one most people outside the scene came to believe.

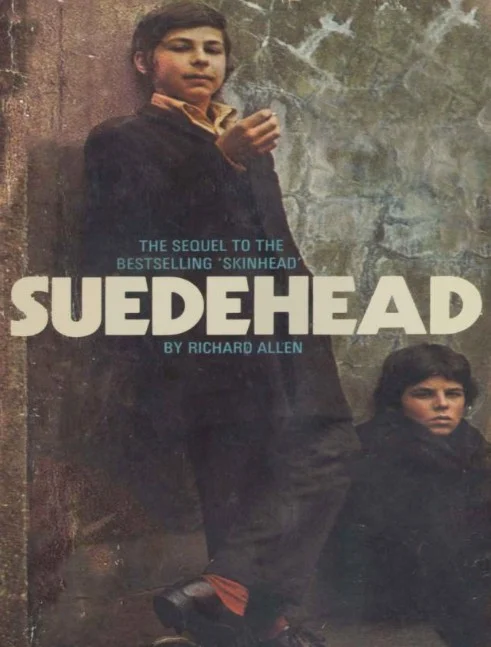

As the starting point of the Joe Hawkins saga, the book sets a template Allen would repeat and escalate through a string of sequels. Each new title would chase fresh outrage and sales. But this debut remains significant as the first pulp attempt to capture the skinhead on the page.

Reading Skinhead now, it’s easy to dismiss it as crude exploitation. But it’s also an undeniable cultural artefact. It tells us how the establishment wanted to see skinheads, how publishers knew they could profit from scandal, and how working-class youth were both demonised and glamorised in the process. Joe Hawkins is not a role model, but he is unforgettable—an archetype that shaped decades of myth around the skinhead name.