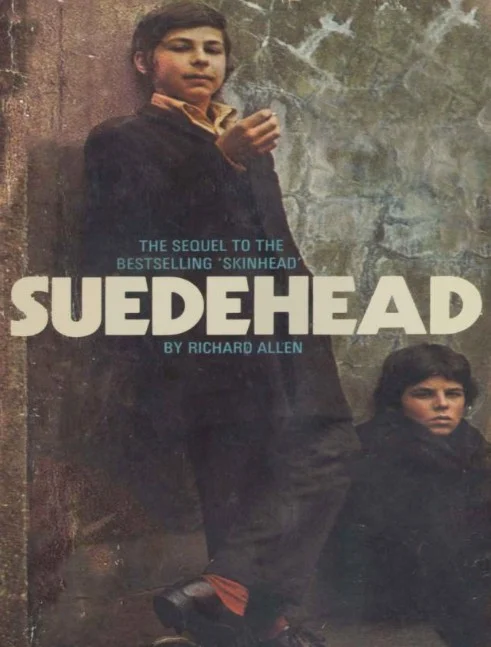

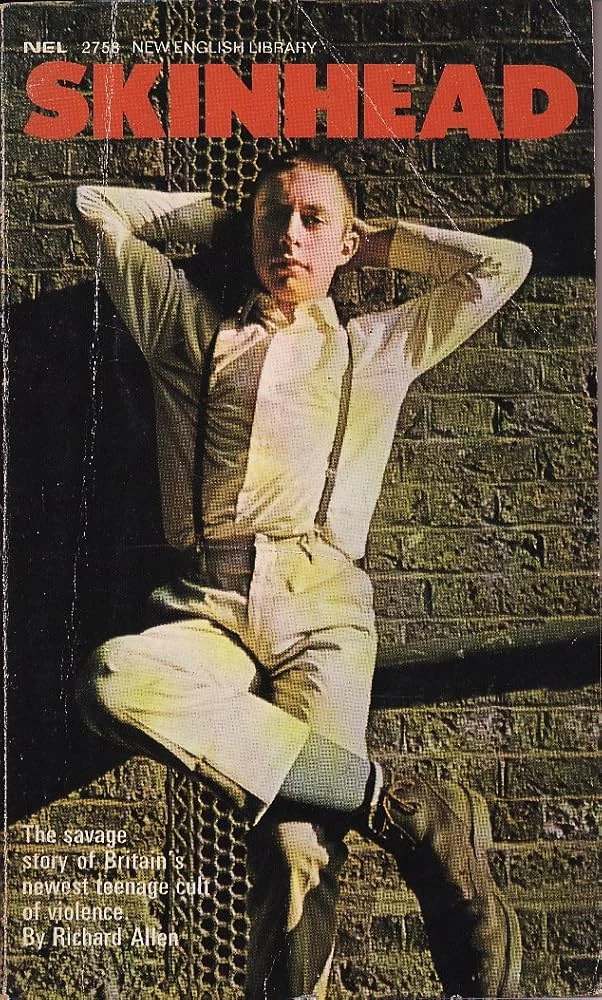

At SKNWRLD we’re starting a new series digging through Richard Allen’s infamous skinhead books, one by one, in the order they were first published. These pulp paperbacks caused outrage in the 1970s, spawning headlines, moral panic, and a cult following that never quite faded. At the centre of it all is Joe Hawkins, the East End teenager whose violent swagger became both a caricature and an archetype of skinhead life. Last time we started of with Skinhead (1970) and now it’s time for the predecessor: Suehead.

Richard Allen’s Suedehead picks up where Skinhead left off, following Joe Hawkins out of prison and into the strange new world of early seventies London. Joe is out of his boots, but not out of trouble. He sheds the cropped skin image and starts growing his hair, reinventing himself as part of the so-called “suedehead” wave – sharper suits, longer hair, a smoother façade. But under the Crombie and bowler, he’s still the same Joe: manipulative, violent, and desperate to climb.

The book opens with Joe staring down eighteen months inside for doing over a copper. The prison chapters show him stripped of his gang, reduced to just another number, and forced to deal with predators and old lags. On release he’s determined never to go back, but his idea of “going straight” is still riddled with schemes. Richard Allen sets him up with Bernice Hale, a well-meaning probation worker whose mix of motherly instinct and sexual tension is one of the book’s strangest threads. Joe plays her like he plays everyone else, cadging loans and sympathy while plotting his next move.

Much of Suedehead revolves around Joe’s attempt to pass as respectable. He gets a junior clerk’s job at a City firm, wears a Crombie and pinstripes, and mixes with girls from better backgrounds – most memorably Lois, a posh virgin who both fascinates and frustrates him. Yet the performance always cracks. Joe’s working-class aggression, his contempt for authority, and his obsession with control keep spilling through the veneer. His rise into the suedehead look is less a transformation than a camouflage.

Joe’s rise into the suedehead look is less a transformation than a camouflage.

Allen’s writing once again mixes tabloid sensationalism with grubby detail. The Soho porn empire, the seedy landladies, the pub encounters with dollybirds – all feel ripped from a world of moral panic headlines. Joe Hawkins isn’t a character to admire, but Allen makes him magnetic enough to follow. Compared to Skinhead, the sequel is more ambitious, giving Joe bigger stages – the City, Soho, Bayswater – and pitting him against subtler forces than just football terraces and street fights. Yet the themes are familiar: sex, violence, class resentment, and the lure of an identity built on image.

Reading Suedehead today, you see it less as a glorification of suede culture and more as a grim social document. The suedeheads were a real shift in style, bridging skins and the early soul boys, but Allen filters it all through Joe’s hunger for status. What the book captures best is the tension of youth trying to break free of its background, only to drag the same instincts along. Joe wants a bowler hat, a City wage, and middle-class girls – but he still dreams in the language of gangs and power.

What the book captures best is the tension of youth trying to break free of its background, only to drag the same instincts along.

Suedehead isn’t subtle, but it doesn’t need to be. It’s pulp fiction rooted in its time: the early seventies, when the skinhead cult was said to be fading but still haunted British streets and headlines. As a sequel it keeps Joe alive, shifts the uniform, and proves Allen could milk his creation for more stories. Whether you take it as exploitation, social commentary, or just a lurid read, it’s part of the myth of Joe Hawkins – the eternal rude boy who refuses to fade out.

Released: November 1971